Illegal logging.

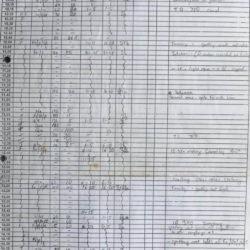

The felling was not a singular incident. The year before, a camera trap had recorded a female orangutan with her infant and teenager. Not long after, the camera display showed the trees in the same area being felled. ‘We had the destruction right in front of us,’ a conservationist said with sadness. Using heavy machinery from a local sawmill, villagers had cut down a patch of forest that contained valuable hardwood. Some conservationists’ main concern was that the ‘illegal logging’, as they framed it, had destroyed important orangutan habitat. However, for these villagers, ‘working logs’ (mambatang), as they are locally known, enabled them to make a living in the face of precarious livelihood pressures by using their own customary forest resources. For them, the continued right to log was as much a moral as an economic concern.

This episode points to the tensions that can arise between customary ways of engaging with the environment and framing access to and ownership over resources on the one hand, and state regulations that define these understandings and the activities as illegal on the other. While local people based their territorial claims on customary law (adat), the management of the site drew on state documents to guide its work. This created a complex, fraught space in which the conservation project had to operate.

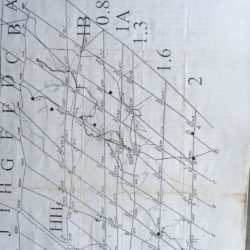

Due to the existence of such parallel legal systems and poor land-use planning in Borneo, territorial disputes like these frequently arise. Before the conservation organisation arrived, the area had been designated for conservation purposes without in-depth investigation on the ground. Officials had demarcated the location of the site using a map in a remote government office. Feeling dispossessed of their land, some villagers began to challenge the protected area and its boundaries. Access to the forest is vital for local livelihoods and land is the most valuable asset villagers have. But what seemed to enrage these villagers even more was the sense they had not been sufficiently involved in and benefitted from the creation of the site. While a few inhabitants were hired as staff, many villagers bemoaned what they saw as the scheme’s top-down approach and lack of information, opportunities for participation, and benefits to the community at large. The case at hand shows that in order to make conservation work on the ground, it is necessary to address the multiple, complex layers in which it takes place. Often, it is not enough to provide jobs or run short-term programmes to improve local livelihoods. To engender positive changes and make conservation work locally, the underlying drivers of structural poverty, social injustice and uneven distribution of wealth and resources need to be addressed. Moreover, the villagers’ concerns show that for them, the creation of long-lasting relationships of mutual acknowledgement, trust and care, and reciprocity are essential if they are to engage with conservation measures. This story reveals how conservationists everywhere need to find ways of engaging in long-term commitments, providing adequate returns, and showing a heightened sensibility to customary rights and norms (adat).