Repelling animals.

‘Woooe-hoooe’, yells Isak, playfully announcing his presence to unseen others. Human voices respond from multiple directions, mixing with the sounds of water, insects, and birds. We cross a stream and climb the wooded hills behind the village. Isak calls out the names of fruit trees, planted when this forest was last ‘opened’ for rice cultivation. ‘When there is too much ripe fruit, we let it rot, as fertiliser, because we’re unable to sell’. The market is too distant.

After 30 minutes we reach what Isak calls ‘kampung durian’ (durian village). It is a sprawling settlement. A hut near each durian tree, in which families wait for the ripe fruit to come crashing down one at a time. Women and children cleave open the spiky shells and place the soft, creamy flesh in plastic buckets, where it is left to ferment with some salt. The result, tempoyak (fermented durian eaten as an accompaniment to rice), will keep the whole year.

After someone shows me a durian that has been half eaten by an orangutan, Isak takes me up the next hill. In a clearing stands a tall durian tree that he claims his family has tended (menjaga) for 7 generations (Isak being of the 4th generation). Last year it gave between 400 and 500 durian, he says, resulting in over 50 litres of tempoyak.

This year, an orangutan has been feasting in this tree, leaving much less fruit for Isak. He points out several orangutan nests. ‘The orangutan usually only comes when we are not here, for example before the fruit is ripe. It does not harm us, it is afraid of us,’ Isak explains. He continues, smiling: ‘Orangutans and humans are connected [menyambung]. We both eat durian. They eat up there, and we eat down here’.

Nevertheless, he needs more durian for his 7 children, all of them living outside the village and relying on their parents for tempoyak. That is why he has cut down the surrounding trees. Next year, there will be no way for an orangutan to reach the tall branches of the durian tree.

Isak’s act of cutting down trees typifies the nature of human-orangutan co-existence in this more-than-human landscape. In contrast to those tourists and scientists who seek direct observation of wild orangutans, most villagers and orangutans in this area prefer to remain mutually invisible. They interact mostly through traces in the landscape, which mediate their relations. When an orangutan left bite marks in durian fruit and nest structures in tree branches, Isak responded by creating a gap in the forest canopy to prevent its return.

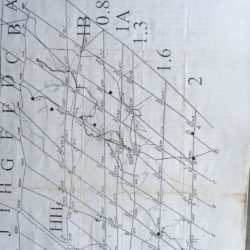

As we descend along the other side of the hill, we pass the spot where this photograph was taken. The animal repelling device makes visible another important medium of invisible co-presence: sound. By rearranging natural elements of the landscape—streaming water and bamboo—people leave an auditory trace in the landscape, a repetitive thwack to scare away animals, such as hungry orangutans.