Orangutans sometimes need to be ‘rescued’ from plantations, villages, farms and orchards, degraded forests, and other situations where their safety and well-being are at risk. Such ‘evacuations’ are usually a last resort and carried out by trained teams who bring with them many crucial skills, including strength, agility and a keen understanding of animal behaviour and pharmacological effects. Veterinarians play vital roles in these procedures, particularly in deciding whether to translocate or rehabilitate the orangutan in question. Of the many things that a vet on the team might need during an evacuation, the medical bag is the most precious and important. The medical bag is required throughout the rescue procedure: at the very beginning to prepare the tranquilizer for the orangutan, for medical checks in the middle, and to ensure that the rescued orangutan is safe and ready for its journey at the end of the operation. Here, we see members of the Orangutan Information Centre’s Human-Orangutan Conflict Response Unit working over their medical bag, which they liken to the popular cartoon robotic cat Doraemon’s magic gadget-filled pocket!

Protocols

The medical bag (Sumatra, Indonesia)

Orangutans sometimes need to be ‘rescued’ from plantations, villages, farms and orchards, degraded forests, and other situations where their safety and well-being are at risk. Such ‘evacuations’ are usually a last resort and carried out by trained teams who bring with them many crucial skills, including strength, agility and a keen understanding of animal behaviour and pharmacological effects. Veterinarians play vital roles in these procedures, particularly in deciding whether to translocate or rehabilitate the orangutan in question. Of the many things that a vet on the team might need during an evacuation, the medical bag is the most precious and important. The medical bag is required throughout the rescue procedure: at the very beginning to prepare the tranquilizer for the orangutan, for medical checks in the middle, and to ensure that the rescued orangutan is safe and ready for its journey at the end of the operation. Here, we see members of the Orangutan Information Centre’s Human-Orangutan Conflict Response Unit working over their medical bag, which they liken to the popular cartoon robotic cat Doraemon’s magic gadget-filled pocket!

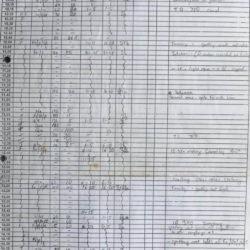

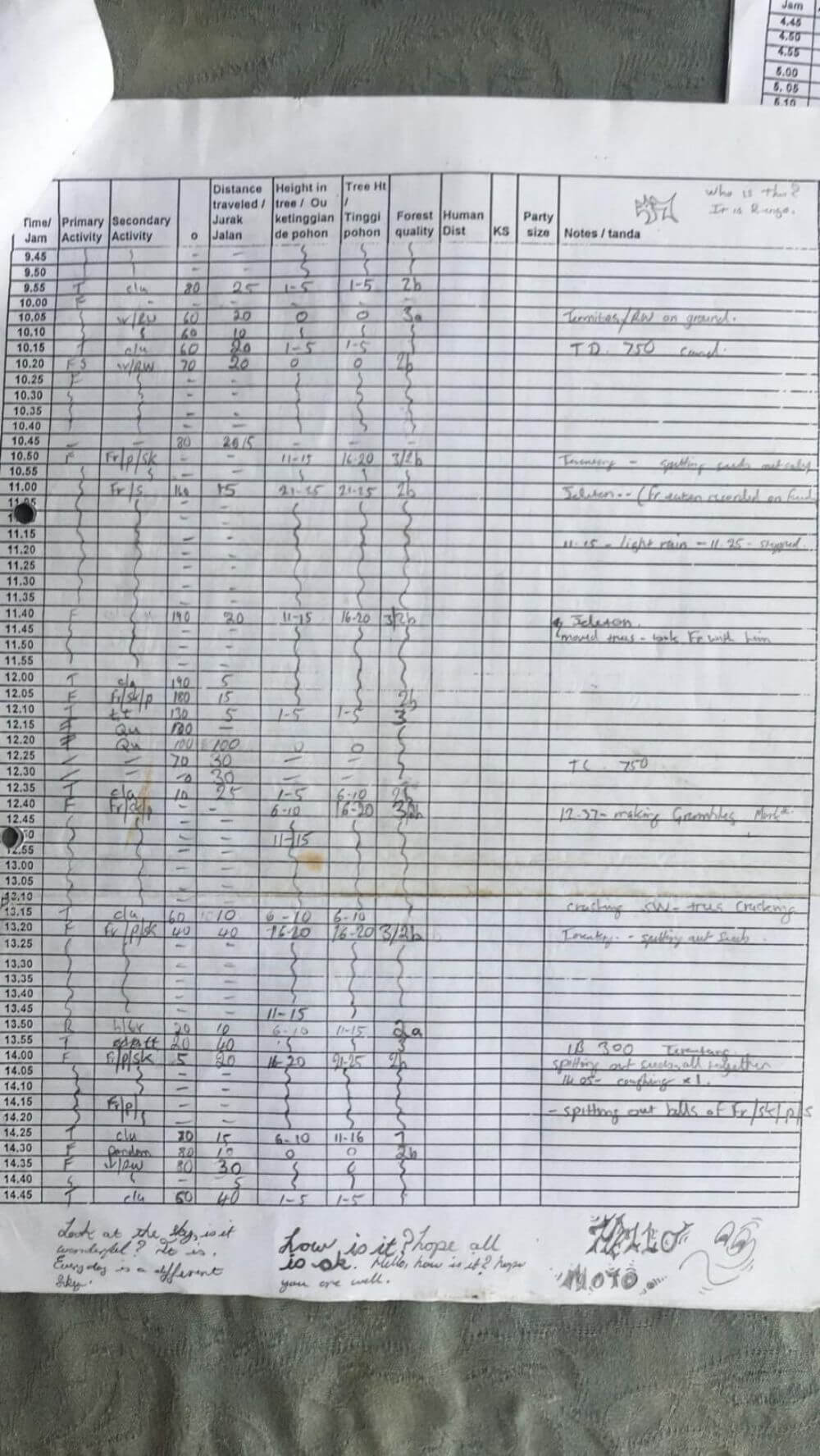

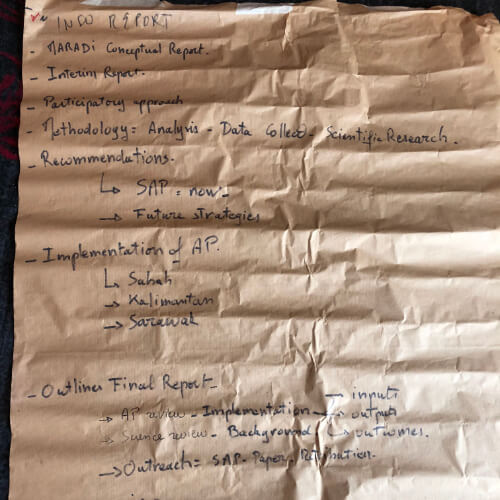

Anaesthetising orangutans: an excerpt from official orangutan rescue protocols.

Orangutan rescue teams in Indonesia are equipped with and need to follow a detailed set of official procedures and instructions. Here we present a translated excerpt from the official government guidelines for anaesthetising wild orangutans prior to moving them. These give us a glimpse of skill and flexibility demanded by such rescues, as well as rescuers’ own emotional involvement in these exercises.

4. Anaesthetising

When the position of the orangutan has become visible and has been blocked off, the rescue team should swiftly estimate how heavy the orangutan is so that they can quickly fill the syringe with the appropriate number of doses of anaesthetic. Several things must be considered at this stage:

a. Estimate the weight of the orangutan’s body.

b. Calculate how many doses of anaesthetic must be prepared (following methods of estimating dosage).

c. Immediately prepare two anaesthetic doses in two separate syringes in case the first shot does not hit the target.

d. Ensure that the anaesthesia needle is not blocked, and that it is tightly attached and covered with the rubber seal.

e. Ensure that the air connectors are completely filled and do not leak.

f. Put the syringe that is ready to be fired into the tranquilizer gun and make sure the back cover is tight.

g. Ensure that the safety mechanism of the tranquilizer gun is locked before pumping pressure into the weapon.

h. Estimate how far away the orangutan is to determine the amount of bars of pressure in the weapon.

i. Find a comfortable and safe shooting position.

j. Find a target that is appropriate and safe, try to aim for the thighs, or at least the upper back or rear parts of the orangutan’s body.

k. Never shoot from the front/facing the orangutan, the risk of hitting the face, genitals or belly of the orangutan is too great.

l. Only when you are certain that you and your target are in the correct positions should you unlock the safety mechanism of the gun and shot.

m. After the shot has hit the target, look and make sure that the drug has entered and carefully observe the orangutan’s reaction to the drug.

n. Meanwhile the others [team members] should be already standing by below with the net to prevent the orangutan from falling directly to the ground.

o. Make sure that there are no dangerous tree stumps or bumps below.

All team members must master their respective skills and have strong instincts (senses), because in the field, things don’t always work out as planned. For example, we may have already prepared the net below, but in the moment that the orangutan falls, its hand or feet might still hold onto or get stuck behind another branch, so that the orangutan falls far away from the prepared net. Sometimes, also, before being completely tranquilised, the orangutan may climb very high, look for a place in the branches or even get into a nest, and thus will not fall, so that a team member must climb the tree to get the orangutan. For things like that, therefore, climbing equipment must also always be prepared so that the safety of the team member as well as the orangutan itself is guaranteed. However, there are also incidents that make the rescue team laugh and feel happy. There have been several orangutans that, before being totally anaesthetised, slowly climbed down from the tree to the ground, until all that remained to do for the team below was to catch the orangutan, put it directly into the cage when the car was nearby, or put it in the net for carrying when the car was far away. Many unique and strange incidents have been encountered in the field.

From FORINA, BOSF, YOSL-OIC, PANECO-YEL-SOCP, IAR INDONESIA, YP, FZS, RHOI, OF-UK, COP, UNMUL, UNAS, BKSDA. 2013. ‘4. Pembiusan’. In B. Tahapan Pelaksanaan in Panduan Rescue (Penyelamatan) Orangutan Liar. Jakarta: Kementerian Kehutanan, Direktorat Jenderal Perlindungan Hutan dan Konservasi Alam Direktorat Konservasi Keanekaragaman Hayati, pp. 14-15.